|

Scarica

(solo in italiano): |

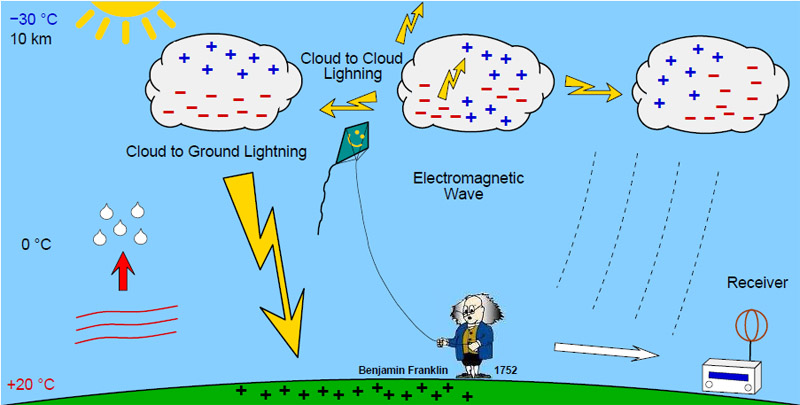

The phenomenon of

lightning is actively investigated since 1752, when the American

statesman and scientist B.Franklin one of the first established

the electrical nature of lightning. As a whole the picture of

formation of lightning is as follows. The terrestrial atmosphere

is very good dielectric located between two conductors - a

surface of the ground from below and the top layers of an

atmosphere, including an ionosphere, from above. These layers

are passive components of a global electric circuit. Between

negatively charged surface of the ground and positively charged

top atmosphere the constant potential difference of about

300.000 V is supported. According to the idea for the first time stated by Wilson in 20th years this

ionosphere potential arises from thunder-storms which create

global electric "battery". Lightning is a visible electric

charge coming from a cloud, going to either another cloud or the

earth. Usually, thunder like the sound you are hearing

accompanies lightning, especially during a thunderstorm.

Lightning occurs because the bottom of a thundercloud becomes

negatively charged, and repels the negative charge of the ground

deeper in so the positive charge is more towards the surface.

Simple physics says that opposite charges attract, so boom, the

lightning takes a one way trip to the closest positively charged

item- usually a tree, phone pole, or other high object. Despite

of an abundance at present of new devices and methods of

research, the microphysical processes leading to charge of storm

clouds, remain a subject of disputes.

for the first time stated by Wilson in 20th years this

ionosphere potential arises from thunder-storms which create

global electric "battery". Lightning is a visible electric

charge coming from a cloud, going to either another cloud or the

earth. Usually, thunder like the sound you are hearing

accompanies lightning, especially during a thunderstorm.

Lightning occurs because the bottom of a thundercloud becomes

negatively charged, and repels the negative charge of the ground

deeper in so the positive charge is more towards the surface.

Simple physics says that opposite charges attract, so boom, the

lightning takes a one way trip to the closest positively charged

item- usually a tree, phone pole, or other high object. Despite

of an abundance at present of new devices and methods of

research, the microphysical processes leading to charge of storm

clouds, remain a subject of disputes.

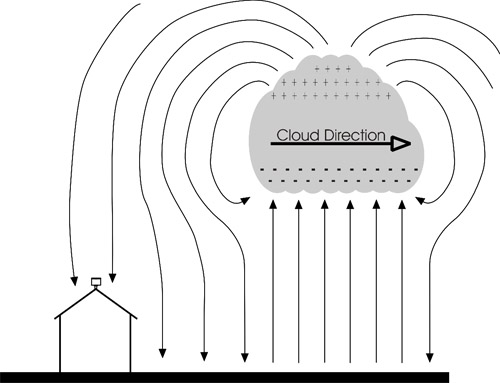

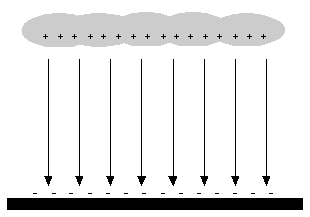

One of hypothesis, illustrated in animation, connects the lightning appearance with solar activity. The Earth’s upper atmosphere interacts with high energy particles from the sun (called the solar wind) to produce a steady stream of positive ions, which, in turn, rain down onto the Earth’s surface. Nevertheless, the Earth’s total average surface charge does not change. The increase in the Earth’s positive surface charge is cancelled out by the flow of negative electrons from the clouds to the ground during electrical storms. A lightning bolt can deliver a current of 10 million amperes to the Earth’s surface. Electrical storms are connected to solar activity. The sun’s activity peaks every 11 years. When solar wind activity is greater, more positive ions are produced by the solar wind. Thus, more electrical storms are induced on Earth to cancel the increased positive ion flow.

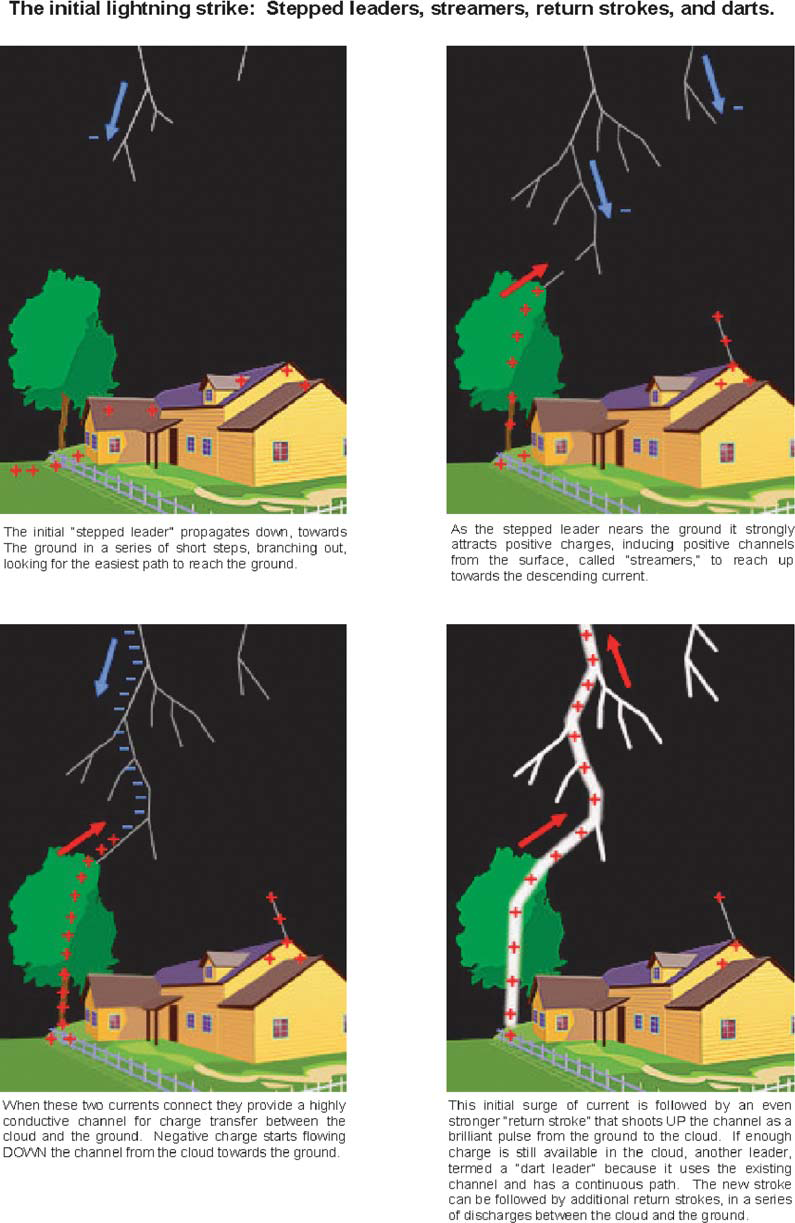

Anatomy of a Lightning Strike

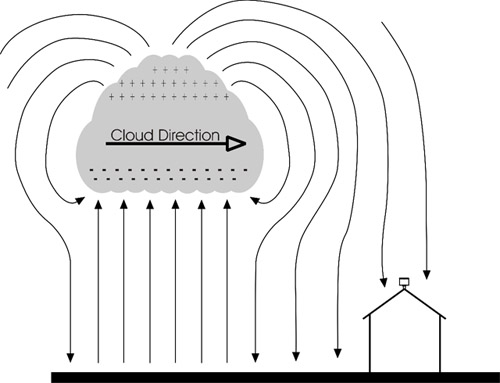

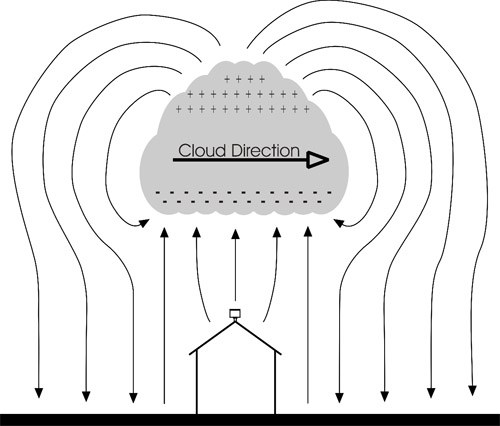

Even in the simple model of a thunderstorm represented in the following

picture, lightning strikes are quite complex.

Both negative

and positive flashes can occur, but negative flashes are

more common. Negative flashes bring negative charge to

the ground, while positive flashes bring positive charge

to the

ground. In negative flashes, the descending current from

the

cloud moves downward in a series of short jumps, called

a

“stepped leader.”

The individual steps in this process

branch

out in different directions, looking for the path of

least resistance

toward the ground. As a leader gets close to the ground,

a corresponding streamer of positive charge moves up

from

the surface to meet the descending negative current.

When

these two currents connect they provide a highly

conductive

channel for charge transfer between the cloud and the

ground.

The initial descending negative charge is followed by an

even

stronger “return stroke” of positive charge from the

ground,

which seems to move up the channel and into the cloud.

The

actual charge transfer is, however, done by free

electrons so the

return stroke is really just a progressive draining of

negative

charge downward, with the upper limit of the drained

path

moving upward as electrons flow to the ground. Multiple

strokes of dart leaders and return strokes can follow,

producing

flickering strobe-like flashes of light.

The entire multiple discharge sequence of a lightning

strike

is normally called a flash and is typically

made up of two to four

separate strokes.

In some cases, as many as 15 or more strokes

have been observed. The subsequent strokes generally

follow

the established conducting channel, but the final strike

point

on the earth’s surface can jump around from strike to

strike,

with separations of up to several hundred meters or

more.

These cloud-to-ground flashes are normally called

CG

lightning,

or simply

ground lightning.

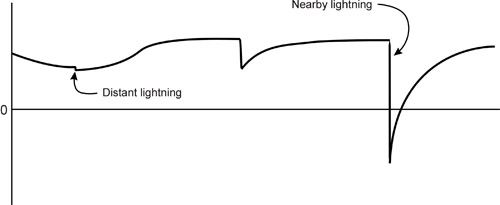

Lightning detection

Cloud discharges and CG flashes both radiate energy over a wide spectrum of frequencies, predominately the radio frequency (RF) bands. During the “stepped” process that creates new channels, there are strong emissions in the very high frequency (VHF) range. High current discharges along previously established channels (“return strokes”) generate powerful emissions in the low frequency (LF) and very low frequency (VLF) ranges. Medium frequency (MF) emissions are centred in the AM radio band and are responsible for the static we hear on AM radio during lightning storms.

AM radio during lightning storms.

Cloud and ground flashes produce significantly different RF emissions over different time scales, which can be used to distinguish between these two classes of lightning. With their high current and predominately vertically oriented return strokes that generate magnetic fields, CG flashes produce strong signals that can easily be associated with a single position near the point they strike the earth’s surface.

When high

currents occur in previously ionized channels during cloud-to-ground

flashes, the most powerful emissions occur in the VLF range. VLF (very

low frequency) refers to radio frequencies in the range of 3 kHz to 30

kHz. An essential advantage of low frequencies in contrast to higher

frequencies is the property that these signals are propagated over

thousands of kilometres by reflections from the ionosphere and the

ground.

Waves with a frequency between 30 and 3 kHz have a length between 10 and

100 km. An applicable antenna for these frequencies is a small loop

antenna of size less than 1/10000 of the wavelength in circumference.

The electric field of the radio waves emitted by cloud-to-ground

lightning discharges is mostly oriented vertically, and thus the

magnetic field is oriented horizontally. To cover all directions

(all-around 360 degree) it is advisable to use more than one loop. A

suitable solution can be obtained by two orthogonal crossed loops as

they are used for direction finding systems.

The size of the antenna can extremely be reduced by using ferrite rods.

But a high number of turns are necessary to reach the same voltage

compared with a loop antenna.

This implies that the ferrite antenna has a lower resonance frequency

than the loop antenna.

The resonance frequency of the ferrite antenna for wide-band VLF

reception should not fall below 100 kHz.

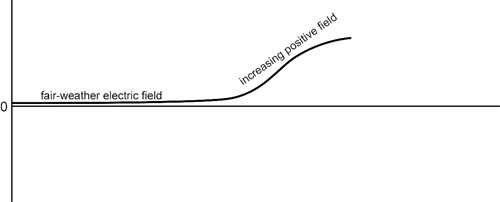

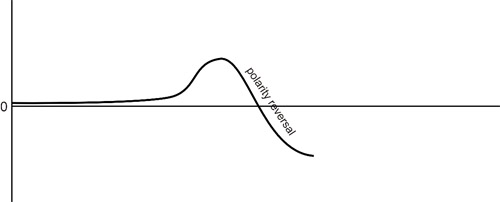

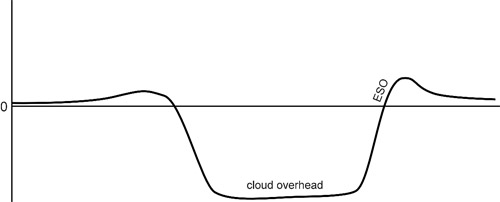

The atmospheric electric field

In the lower atmosphere, the mean atmospheric electric field can be modified due electric charges transport made by convection, corona effect, air humidity and the pollution.According to Ohm’s Law, under fair weather conditions, is possible to describe the atmospheric electric field in function of the current density:

where E is the local electric field (V/m), s is the electrical conductivity of the air and J is the electrical current density (A/m2).

The E.F. in a thunderstorm

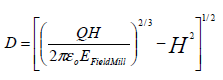

The atmospheric electric field for a region where we have a storm is described for the image method, in which it establishes that one charge configuration near a perfect conducting infinite plan can be replaced by the same configuration, its image and a equipotential surface in the place of the conducting plan.The next equation shows the relation of the lightning distance as function of the local electric field (E), of a charge center (Q) and the charge center height (H):

Sensors to detect lightning activities

| RDF (Radio

Direction finding) Lightning sensor

The DF sensor is an original concept and design by

Frank Kooiman and thanks to the help of

Daniel Verschueren. The electronics consists of

an amplifier which boosts and filters the signal from an antenna

and passes it to the soundcard of a computer (Line-in). The direction can be calculated from the two

signals measured. It is still not possible to say for certain

that the lightning strike occurred at one direction, exactly

opposite direction could also have been possible (+180 degrees).

This is also due to the fact that we do not know if the

lightning strike had a positive or negative charge. If you are

working with a single station, a third antenna is therefore

necessary to detect the charge and therefore the correct

direction of the strike. A single station cannot be used to

determine the

Now I have in test two ferrite antennas just like the ones used for the TOA system. It's not simple to adapt them to the RDF hardware but some good result is coming :-)

You can find information about

Lightning Radar on: |

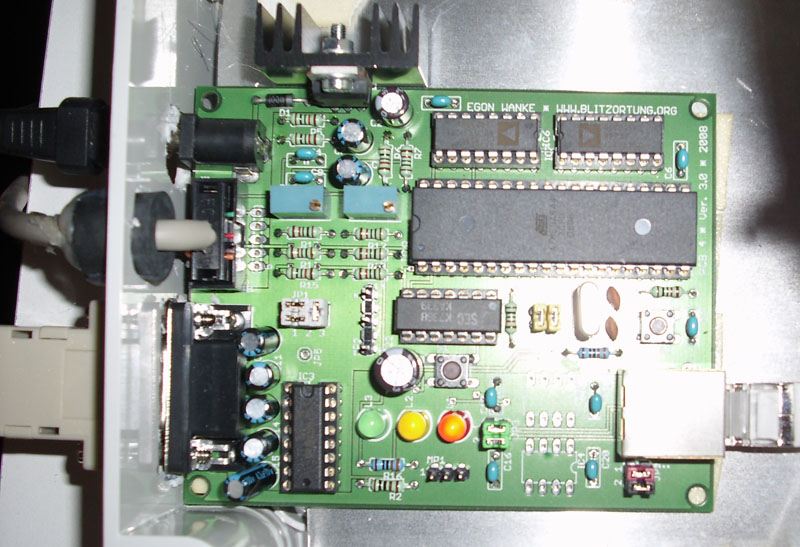

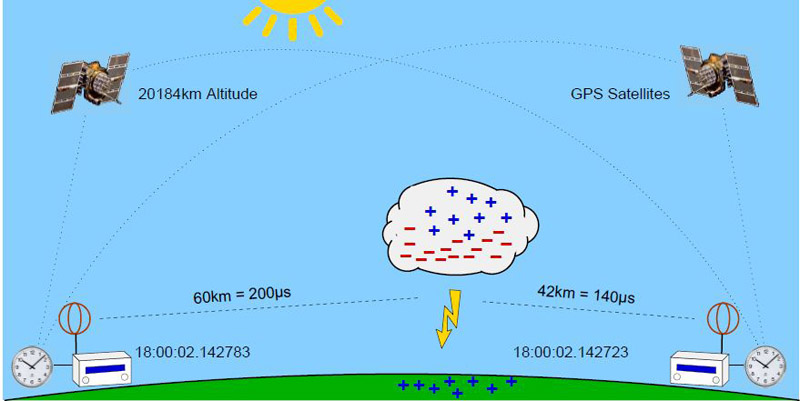

TOA (Time of Arrival)

Lightning sensor

The TOA sensor is developed

thanks to the Egon Wanke

Blitzortung.org project. The TOA (time of arrival)

lightning location technique is based on hyperbolic curve

calculations.

|

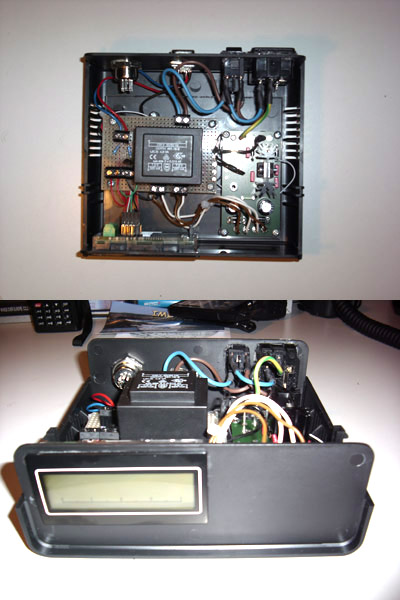

The E-Field Mill

The

E-field mill measures the

static electric field generated

by thunderclouds and can detect the atmospheric conditions which

precede lightning.

by thunderclouds and can detect the atmospheric conditions which

precede lightning.

A field-mill is used to measure an electrical earth field (V/m).

A field-mill is based on static electric influence on a

conductive plate. If an electrode in an E-field is covered by a

rotating wing then the charge is flowing from the electrode to

ground. If the electrode is not covered influence charges are

flowing back to the electrode.

The current is proportional to E-field.

At stable weather E-field is about 100–150 V/m (direction is

from atmosphere to earth). Earth is negative and atmosphere is

positive. During a lightning there are a lot of charge

separations in the cloud. This charging is very strong and under

the lightning cloud the E-field can be up to 30000 V/m. Also

without lightning strokes the

E-field can be very high. This

could be used as lightning warning. Depending on cloud type

(negative or positive cloud base) E-field is positive or

negative.

I've developed the software for the

E-Field Mill in LabView.

With this one I have the possibilities to send data in

graphic images to a specified ftp site, or via socket.

It's possible to filter the data received from the field

utilizing mediated values, inverting the sign and

deciding an Offset.

It's also possible to set two type of alarms, only

visible at the moment, for high alarms and very high

alarms.

I opened a SourceForge project dedicated to the

FEM Software:

https://sourceforge.net/projects/femsoftware/

The voltmeter DPM812

used for the original project has become a discontinued

product.

|

ugh

you can feel your hair stand on end (if this happens outdoors

during a thunderstorm crouch down with your feet together as you

are about to be struck by lightning.) An electric field is

what attracts your hair to a charged comb or a charged balloon.

ugh

you can feel your hair stand on end (if this happens outdoors

during a thunderstorm crouch down with your feet together as you

are about to be struck by lightning.) An electric field is

what attracts your hair to a charged comb or a charged balloon.